On June 12, 1963, U.S. president John F. Kennedy—who would be assassinated only a few short months later—called the white resistance to civil rights for blacks “a moral crisis” and pledged his support to federal action on integration.

That same night, [Medgar] Evers returned home just after midnight from a series of NAACP functions. As he left his car with a handful of t-shirts that read “Jim Crow Must Go,” he was shot in the back. His wife and children, who had been waiting up for him, found him bleeding to death on the doorstep. “I opened the door, and there was Medgar at the steps, face down in blood,” Myrlie Evers remembered in People magazine. “The children ran out and were shouting, ‘Daddy, get up!”‘

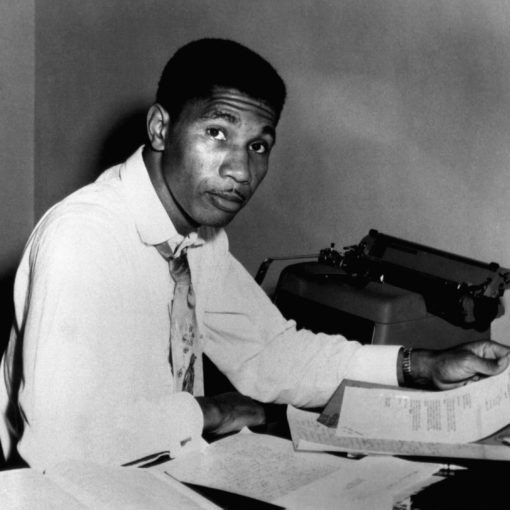

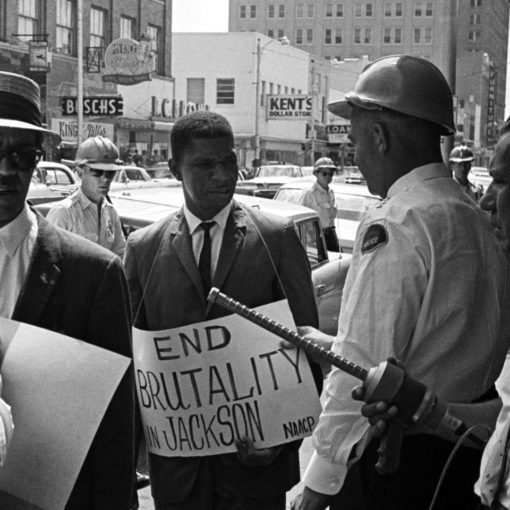

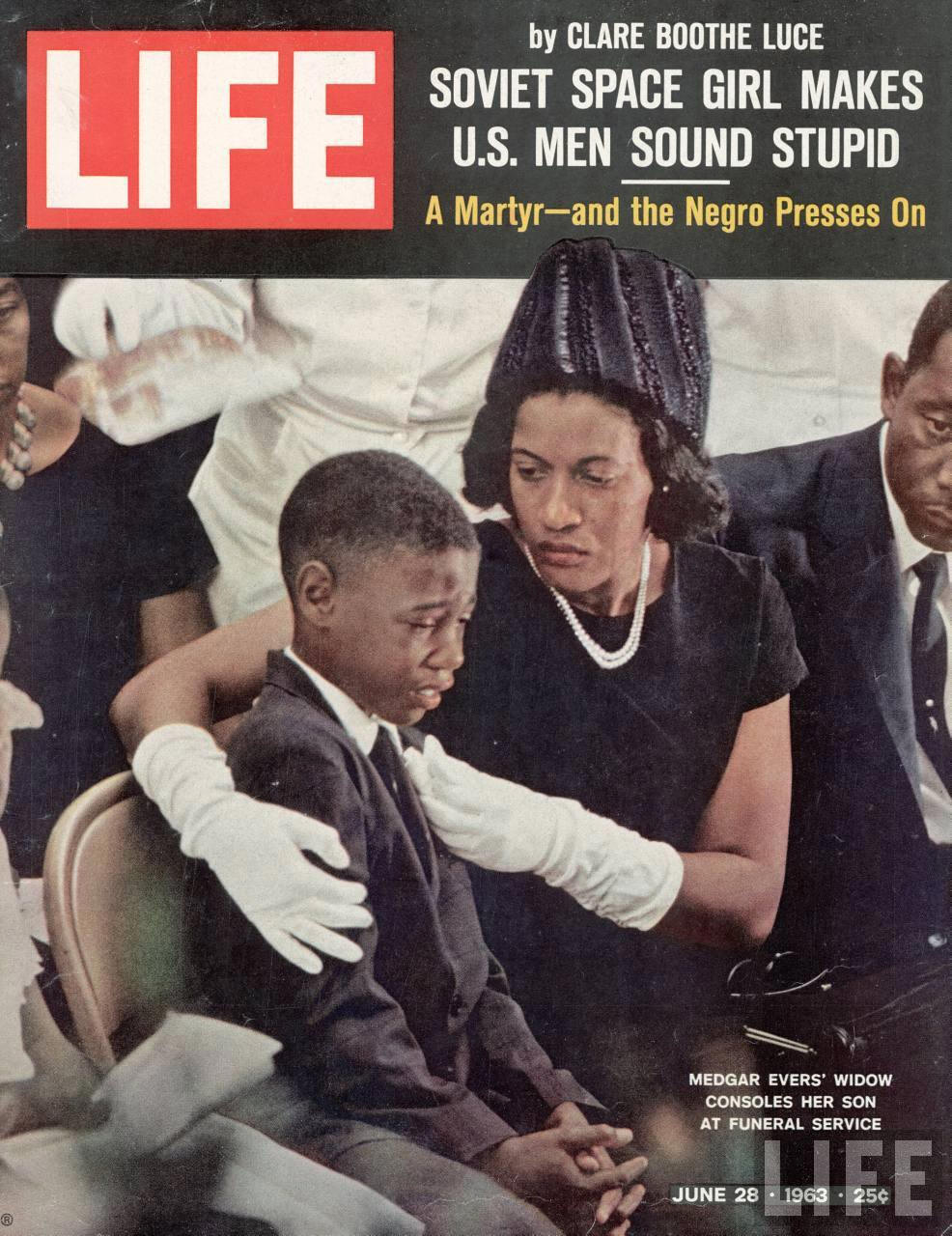

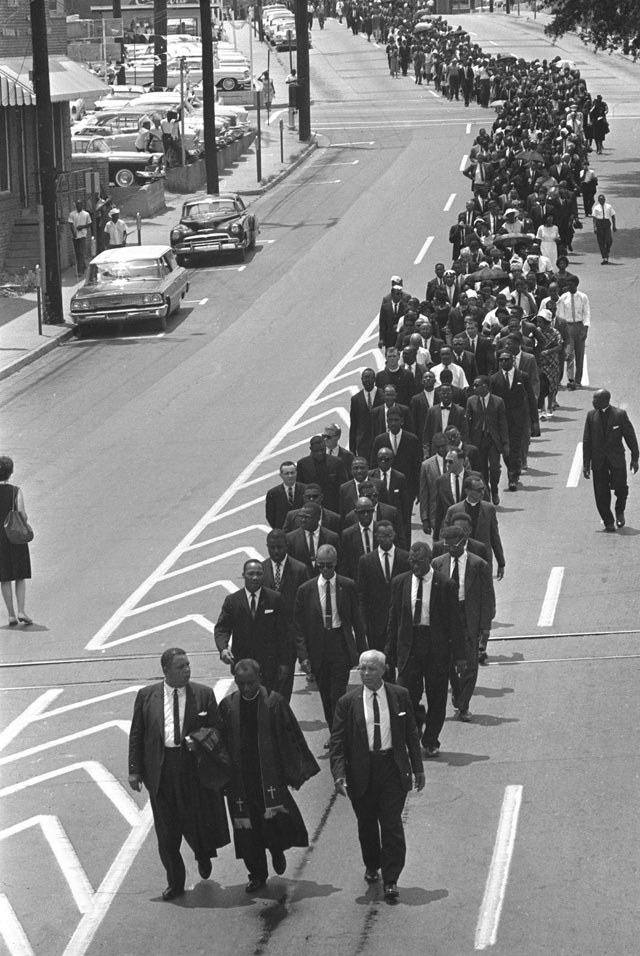

Evers died fifty minutes later at the hospital. On the day of his funeral in Jackson, even the use of beatings and other strong-arm police tactics could not quell the anger among the thousands of black mourners. The NAACP posthumously awarded its 1963 Spingarn medal to Medgar Evers. It was a fitting tribute to a man who had given so much to the organization and had given his life for its cause.

Rewards were offered by the governor of Mississippi and several all-white newspapers for information about Evers’s murderer, but few came forward with information. However, an FBI investigation uncovered a suspect, Byron de la Beckwith, an outspoken opponent of integration and a founding member of Mississippi’s White Citizens Council. A gun found 150 feet from the site of the shooting had Beckwith’s fingerprint on it. Several witnesses placed Beckwith in Evers’s neighborhood that night. On the other hand, Beckwith denied shooting Evers and claimed that his gun had been stolen days before the incident. He too produced witnesses—one of them a policeman—who swore before the court that Beckwith was some 60 miles from Evers’s home on the night he was killed. (1)

The hole in upper right of picture was made by a 30-30 caliber bullet which mortally wounded Medgar Evers, state field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Jackson, Miss., on June 12, 1963. A bullet passed through Evers into the window, which reflects the car where Evers was when he was shot in the back. (AP Photo)

Picture credits: John Loengard—LIFE Images

Picture credits: John Loengard—LIFE Images

This death, coming just hours after a speech on civil rights by President John F. Kennedy, sparked a national outpouring of mourning and outrage.

White policemen wear hardhats and carry double-barrelled shotguns as they block mourners demonstrating at the funeral of slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers, Jackson, June 15, 1963. (Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

In this June 15, 1963, file photo, mourners march to the Jackson, Miss., funeral home following services for slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers. (AP Photo)

See more photos from the funeral here.

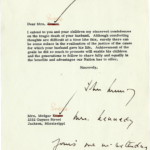

See John F. Kennedy’s first draft, partially handwritten, letter of condolence to Medgar Evers’ widow here.

FBI Records related to Medgar Evers’ murder (The Vault)

(1) “Medgar Evers.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2nd ed. Vol. 5. Detroit: Gale, 2004. 345-348. Gale Virtual Reference Library